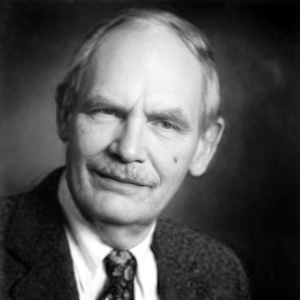

Born in New York City on November 26th, 1919, Frederik George Pohl Jr. was not merely a science fiction author; he was a chronicler of the burgeoning anxieties of the mid-20th century and beyond. His early life, marked by a restless intellect and involvement in radical politics, instilled within him a keen observational eye and a skepticism towards easy assurances—qualities that would define his prolific career. Though initially drawn to fanzines and pulp magazines as an editor and publisher, Pohl quickly established himself as a formidable voice in the burgeoning science fiction field.

Pohl’s influence on the industry was immense. He wasn’t merely writing stories; he was shaping the cultural conversation around technology, consumerism, and the evolving meaning of progress. As an editor at Galaxy and If, he provided a crucial platform for emerging “New Wave” authors like Harlan Ellison and Samuel R. Delany, helping to push the genre beyond its pulp roots. He understood the power of collaboration and mentorship, fostering a community of writers who would redefine science fiction’s possibilities. Authors such as Philip K. Dick acknowledged Pohl’s impact on their own work, recognizing his ability to dissect societal trends with both wit and unsettling precision.

Pohl’s style is often characterized by its sardonic humor, fast-paced plotting, and a relentless focus on the practical implications of futuristic technologies. He eschewed grand philosophical pronouncements in favor of exploring how these advancements would impact everyday life—the advertising, the bureaucracy, and the messy, improvised nature of human existence. This contrasted sharply with the more romantic or utopian visions prevalent in earlier science fiction. Where authors like Isaac Asimov often focused on the elegance of scientific solutions, Pohl was interested in the compromises and unintended consequences that inevitably followed.

His story The Tunnel Under the World, published in 1955, exemplifies this approach. The story, beginning with a disquieting sense of déjà vu and escalating into a chilling exploration of societal control, captured the pervasive Cold War paranoia of its time. It wasn’t about alien invasions or interstellar wars; it was about the subtle erosion of reality through manufactured consensus—a theme that resonates powerfully even today. The story’s unsettling depiction of a world subtly altered by unseen forces served as a potent warning against unchecked corporate power and the dangers of passive acceptance, marking a significant moment in the genre’s evolution towards social commentary.

Pohl’s deft blending of satire and unease cemented his position as a master storyteller. He didn’t offer easy answers or comforting resolutions; instead, he presented readers with a mirror reflecting their own potential futures—and asked them to consider what they might see staring back. He was, in essence, a cartographer of the possible, charting not just where we could go, but also the hidden pitfalls along the way.